Across the Yamuna River in east Delhi, it was a cold, grey, December day in Trilokpuri. But once you entered through the gate, crossed the school playground, climbed the broad staircase to the first floor and entered the first standard classroom, you were warm. Not sure exactly where the warmth came from. Maybe it was the effort of getting there. Maybe it was the sight of so many excited young children in their grey woollen sweaters and colourful woollen caps. Maybe it was the fact that they were all sitting cosily together around their teacher on a bright striped duree[1]. You could just feel the warmth all around.

The children were working with barahkhadi charts. The teacher was sitting on the floor with them. She had a big barahkhadi chart and the children all had smaller charts. Everyone had slates for writing. Chalk and chalk pieces were scattered all over on the duree on the floor. The barahkhadi chart is a grid. The first column in each row is a letter. The rest of the rows is a series of symbols that shows the combination of that letter combined with different vowel sounds. The teacher was saying out loud, a letter-vowel sound from the chart. Children listened. Then they looked for the letter symbol on the chart.

The children were working with barahkhadi charts. The teacher was sitting on the floor with them. She had a big barahkhadi chart and the children all had smaller charts. Everyone had slates for writing. Chalk and chalk pieces were scattered all over on the duree on the floor. The barahkhadi chart is a grid. The first column in each row is a letter. The rest of the rows is a series of symbols that shows the combination of that letter combined with different vowel sounds. The teacher was saying out loud, a letter-vowel sound from the chart. Children listened. Then they looked for the letter symbol on the chart.

Next, they ran their fingers across the row till they found the correct letter-vowel combination. “Write “ची” (chii) said the teacher. Many little fingers moved onto the chart. Some had to lean over and some others crawled a bit to reach the chart. Fingers found “च” (ch) on the chart and then moved horizontally across the row, moving cell by cell. Some found the correct symbol quickly. Others took a bit more time.. “च” (ch), “चा” (chaa), “चि” (chi), and then stopping at the symbol that was “ची” (chii). The right spot on the grid. The children, their charts and slates were all in a compact circle around the teacher. She could see most of the charts and slates from where she was sitting. She could see the finger movements. She could follow the chalk and track the fingers painstakingly writing on the slate. Once most children wrote “ची”, the teacher moved onto the next sound.

The routine was working well. The drill of listening to the sound, finding the correct symbol and writing the symbol on the slate, was working well. Single sounds could easily be found and then written down. So now, the teacher said, “Let’s try something different. Listen to me. “सो-नू” (So-nu). (This was the name of a colleague who was in the classroom with me.) “ध्यान से सुनो मै क्या बोल रही हूँ| तोड़ो – सो – नू| अब खोजो| हर टुकड़े को लिखो| जोड़ कर लिखो|” (Listen carefully to what I am saying. Segment it – so- nu. Now look for each piece on the chart. Write. Join and write.)

The routine was working well. The drill of listening to the sound, finding the correct symbol and writing the symbol on the slate, was working well. Single sounds could easily be found and then written down. So now, the teacher said, “Let’s try something different. Listen to me. “सो-नू” (So-nu). (This was the name of a colleague who was in the classroom with me.) “ध्यान से सुनो मै क्या बोल रही हूँ| तोड़ो – सो – नू| अब खोजो| हर टुकड़े को लिखो| जोड़ कर लिखो|” (Listen carefully to what I am saying. Segment it – so- nu. Now look for each piece on the chart. Write. Join and write.)

This was a new task. Challenge for some. Easy step up for others. There was a new, excited buzz in the classroom. Chatting, pointing, writing, rubbing, writing again. Soon, the word “सोनू” began to appear on the slates across the room. There was fun in being able to write and pride as well. Everyone wanted the teacher to see what they had written. Children wanted to show their friends as well. The teacher was quietly smiling too. She was delighted with what the children could do. It was hard to tell who was enjoying the tasks – she or her children.

Suddenly the teacher pointed to me. All the children stopped and followed her finger. “Let’s write her name,” she said. “Oh no, no” I protested immediately. “My name is hard to write”. My protests were ignored. The teacher sounded out my name slowly and loudly. “रु-क-मि-नी” (ru-k-mi-nii). She repeated it a few times. This time there were many pieces to find. Children were sounding out my name. The sounds echoed around the classroom, softly and loudly. The room became warmer with so much activity. I was convinced that writing ““रुकमिनी” was harder than writing “सोनू”. But no one seemed particularly bothered. They continued to focus happily on their task. It just took a little more time, a little more patience and a bit more persistence. For some, it meant watching their friends attentively. Just like with ““सोनू” (Sonu), my name began to appear on slates.

For those who wrote big, the name took up the entire space. Others fitted my name neatly under ““सोनू”. Since it was my name, it was important to come up and show me the work. With each child who came up to me, my amazement increased. More than what I saw written in the small slates, I was amazed by children’s confidence in their own ability and the teacher’s belief in her own children.

For those who wrote big, the name took up the entire space. Others fitted my name neatly under ““सोनू”. Since it was my name, it was important to come up and show me the work. With each child who came up to me, my amazement increased. More than what I saw written in the small slates, I was amazed by children’s confidence in their own ability and the teacher’s belief in her own children.

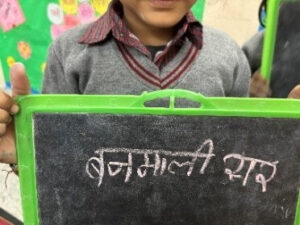

Armed with their own barahkhadi charts, children seemed capable of writing anything. By the time we left the classroom, they had written “बनमाली” (Banmali) – the name of another colleague who was with us. Without prompting, some had added “सर” (sir) after his name. One little girl pulled at my sweater. She explained that since there was no place on her slate after ““बनमाली” (Banmali), she had written “सर” (sir) in front of his name.

There was a hum of happy activity. Cosy and comfortable on the duree. A busy mix of charts, chalks and slates. Listening and chatting, reading and writing. Jumping up to show the teacher. Sitting down next to friends. It did not matter what the weather was outside. By the time we left the classroom, the group had moved on to sentences. From the warmth of their classroom, they started writing “आज सर्दी है” (today is cold).

– Dr Rukmini Banerji, CEO, Pratham Education Foundation

[1] Duree is a big, thick, cotton, woven mat, commonly used as a rug or floor covering.PS: This write-up has been published in its original form without any editing or alterations. Any grammatical errors, typos, or stylistic variations are preserved to maintain the authenticity of the author’s work. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the individual authors and do not reflect the views or positions of the organisation.